Station 1 | Maryland Street, Stanthorpe

The Piazza, Stanthorpe

Find a place in the town of Stanthorpe where you can sit and observe people going about their daily business.

Perhaps the Piazza in Maryland Street would be a suitable place or a spot along the 5 km walk along Quart Pot Creek.

You are watching but not participating.

Murals around the town hint at the life of the people from this region since Europeans arrived. Look for the names of artists.

What do you notice?

Station 2 | Lions Park, Quart Pot Creek

Is there a question bubbling up for you?

Who may have walked this way before me?

Who are my companions on the way?

Where to from here?

Where am I going?

Do I need to change direction?

When I am lost who can help me find my way again?

From where can I get directions?

How far is it?

Are we there yet?

Song “Wherever I go”

Wherever I go, whatever I do,

whoever I am, I’m going with you.

No matter the time, no matter the place, however I move,

you walk at my pace. On every day of every year

the weather may change,

but you’re still here.

Jesus, you’re the light for the journey,

you’re the destination and the road.

You provide the signs along the highway,

you’re the best companion I know.

We could be delighted or dejected,

at the beach or standing in the rain,

Jesus, you will never ever leave us,

we can trust your blood and your pain.

Take all our fear,

make us brave, make us strong; earth is our home,

this is where we belong.

From where you’re sitting, on the opposite side of the creek, and the opposite side of Carnarvon Bridge, there is a rose garden honouring remarkable women of the Granite Belt. As you approach Station 3, if you like, take a detour to admire this garden. It will likely be visible from the benches near the Visitor Information Centre at your next stop as well.

Station 3 | Information Centre Park Benches, Quart Pot Creek

Time of First Contact between Europeans and First Peoples

Find a seat on the Quart Pot Creek walk way and take some time to read about the First Peoples of this region: the Kambuwal (Gambuwal) people.

The time of first contact

Article for “Free Times” By ROBERT MACMAURICE, 05 November 2015

PROBABLY the first European person to meet a Kambuwal person (Gambuwal and other variations of spelling are also documented) was Allan Cunningham on 13 June 1827. He described it in his journal in the following way: “Although very recent traces of natives were remarked in different parts of the vale, in which we remained encamped about a week, only a solitary Aborigine (a man of ordinary stature) was seen, who in wandering forth from his retreat in quest of food chanced to pass the tents. Immediately however, upon an attempt of one of my people to approach him, he retired in great alarm to the adjacent brushes, at the foot of the boundary hills, and instantly disappeared. It therefore seems probable that he had not previously seen white men, and possibly might never have had any communication with the natives inhabiting the country on the eastern side of the Dividing range, from whom he could have acquired such information of the existence of a body of white strangers on the banks of the Brisbane, and their friendly dispositions toward his countrymen as might have induced him to have met with confidence our overtures to effect an amicable communication…”.

That person would have been a Kambuwal tribal member. What he reported to others would also have been interesting for the historical record. The Kambuwal people lived in an area of 9600 square kilometres, from Bonshaw, Inglewood, Millmerran, Leyburn, east of Stanthorpe, the western slopes of the Great Dividing ranges, and Tenterfield. The Kambuwal people were surrounded by other peoples including the Jukambul, Ngarabal, Kwiambal, Bigambul, Giabel, Keinjen, and Kitabal. Crossing the borders of tribal lands, without permission, could lead to punishment of the infringer. Allan Cunningham and his party of six men and 11 horses, in all innocence, had to cross many tribal boundaries in his 1827 journey from Sydney to his discovery of the Darling Downs and back. During the 14 week journey he only observed Aborigines on five occasions. Perhaps the strangeness of these white people held the landowners back. It was Allan Cunningham’s discoveries that led to many other people arriving on the Darling Downs eager to claim land. The fact that Aboriginal people had lived in this land for thousands of years was of no concern to them.

In early 1840, Patrick Leslie and a convict companion known as Murphy, were possibly the second Europeans to be sighted by the Kambuwal people, when they traversed a number of tribal lands. Patrick Leslie followed the same western pathway from Sydney, as did Allan Cunningham, and then criss-crossed the Southern Downs area looking for his ideal piece of land. The land that he took up was to become known as Toolburra Station and Canning Downs Station, which he stocked with sheep in late 1840, and later he acquired Goomburra Station in 1847. This was the land of the Keinjin people. Patrick Leslie was noted as a “hard” man and he did not have good relations with the local Aborigines. On one occasion he was attacked by Kambuwal people, who wished to murder him, but ironically was saved by some Keinjin people who were working as stockmen on his property. The reason for the Kambuwal attack was that a number of Kambuwal women had been raped by one of Patrick Leslie’s workers.

The next European that encountered the Kambuwal people was Matthew Henry Marsh and his three companions who came up from Sydney through the New England plateau. They camped at the present site of Maryland Station on 17 January 1842. In exploring the area around The Summit through to present-day Stanthorpe they became aware of about 500 Aboriginals in the area. These Aboriginals would have been Kambuwal people. In another camp near the present Stanthorpe township the four men spent a fearful night, when they saw numerous fireflies, which they fearfully imagined as Kambuwal people coming to attack them. In daylight they recognised their mistake and as a result named the place Funker’s Gap, which is still the place name today. Funk being an old-fashioned term meaning panic or to be terrified.

Fear was probably the main emotion that Europeans experienced with Kambuwal people and other Aborigines. This fear led to atrocities, but for every European who died many more Aboriginals died in revenge. Some estimates put the number of Kambuwal people at around 1500 at the time of European invasion. These numbers appear to have rapidly declined, as occurred in other tribes as well, with the presence of Europeans. In the 1850s for instance, at the Golden Fleece Tavern, which was located where the township of Stanthorpe is now, there were reports of regular encampments of about 300 Kambuwal people on Quart Pot Creek. By the time of tin discovery and the formation of Stanthorpe in 1872, this was no longer the case.

In 1874 the then 14-year-old George Bamberry, who lived at Wylie Creek, discovered a Bora ring about two kilometres east of Ruby Creek. It was apparently last used by the Kambuwal people about 1873. Other Bora rings exist in the region.

About 100 Kambuwal words and a few expressions were recorded by Mrs Harriott Barlow during the 1850s and 1860s. “Wallangarra” meaning, long water hole and “Yandilla” a small town to the east of Millmerran, meaning running water, are two examples of surviving Kambuwal language. Other surviving traces of the Kambuwal people include stone implements and particular sites known to have been significant to them. Kambuwal people were relocated as far away as missions on Fraser Island, and perhaps Cherbourg and Deebing Creek Mission (near Ipswich), with the break-up of their social and cultural living patterns. How many descendants are there today?

Beyond this the Kambuwal people and their knowledge and customs appear to have disappeared. Lost because of fear and the insatiable pursuit of land and fortune that the first Europeans saw in this land of opportunity.

Originally accessed by Kaye Ronalds on May 2, 2018, from: https://freetimes.com.au/stories/2015-11-05/the-time-of-first-contact/

Station 4 | Soldiers’ Memorial, Lock Street

Built around 1926 the orientation allows the morning sun to come in from the east and the setting sun to flood the shelter with the evening light. The design reflects the words of the Ode;

“We shall grow not old

Laurence Binyon

as those who are left grow old,

age shall not weary them

nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun

and in the morning, we shall remember them.”

Stanthorpe Soldiers’ Memorial, Lock Street

Station 5 | Catholic Church, High Street

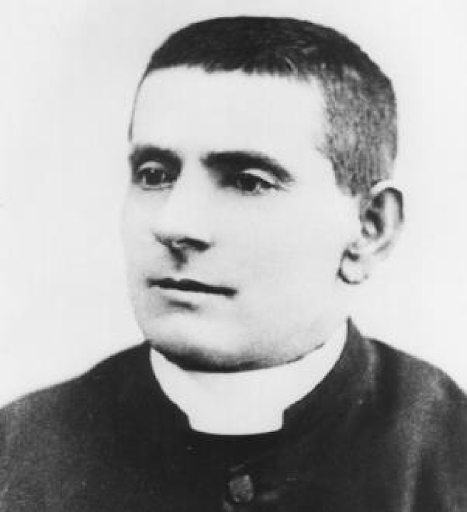

In front of the Catholic Church is a memorial to Fr Jerome Davadi.

For what is that Roman Catholic Priest remembered?

Father Jerome Davadi. Priest of Stanthorpe Catholic Church 1874-1900

A memorial to Father Davadi, Catholic Church, Stanthorpe

It is not often that you find a memorial to a priest in the main street of a town. Father Jerome Davadi who was the Catholic priest in Stanthorpe from 1874 until his death in 1900.

“He was able to foresee the problems of settlers as income from tin petered out. He brought knowledge of the culture of vineyards and the making of wine from his homeland of Italy. He converted his horse paddock at the Presbytery into a vineyard. He planted another vineyard at the foot of Mt. Marley, later to become known as ‘Vichie’s Vineyard’. He also acquired further land to plant apricot and peach trees some of which are still alive today. Father Davadi encouraged his parishioners to plant fruit on the Granite Belt by giving them cuttings from his own nursery and offering financial assistance.”

Accessed April 26, 2018 at:

http://www.stjosephs.qld.edu.au/davadi.html

Imagine how Father Jerome Davidi taught from John 15 and the words of Jesus, “I am the True Vine and God the Father as the vine dresser.” The metaphor helps us recognise that the whole of God’s people make up the vine and are incorporated into Christ. We cannot be the Church without that connectedness.

You are the vine, we are the branches,

Danny Daniels & Randy Rigby

keep us abiding in you.

You are the vine, we are the branches,

Keep us abiding in you.

And we’ll go in your love

and we’ll go in your name,

that the world, will surely know,

that you have power to heal and to save.

“We are a pilgrim people,

always on the way towards a promised goal;

on the way Christ feeds us with word and sacraments,

and we have the gift of the Spirit

in order that we may not lose the way.”

From the Basis of Union Uniting Church in Australia

Station 6 | St. Joseph’s School, Cnr High & Corundum Streets

Sculpture of Jesus in the St. Joseph’s School grounds, Stanthorpe. Created by Timothy Schmalz

In which seat would you choose to sit? Why?

Where might Jesus invite you to sit?

Timothy P. Schmalz is a well-known Canadian sculptor based out of St. Jacobs, Ontario. His work mainly consists of monumental religious art. His Catholic faith is a deep source of inspiration for his work.

Schmalz has said, “If my sculptures are used by people as a tool to think, then I’m very happy. His stated artistic goal is: “Creating art that has the power to convert. Creating sculpture that deepens our spirituality. Attaining these two goals describes my purpose as an artist.”

Timothy Schmalz has sculpted a similar cast bronze which he called “The Last Supper.” It is at the St. Emma Monastery in Greensburg, Pennsylvania. The 12 empty stools invite visitors to sit with Jesus as he breaks bread. The sculpture also is displayed outside Old Stone Church in Cleveland, Holy Spirit Catholic Church in Brighton, Michigan, St. James the Greater Church in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, St. Christopher Church in Indianapolis and elsewhere.

Read more about this artist and the impact of his Sculpture. Timothy P. Schmalz also sculpted the famous “Jesus the homeless.”

Refrain:

Carey Landry

We are companions on the journey,

Breaking Bread and sharing life;

and in the love we bear is the hope we share

for we believe in the love of our God,

we believe in the love of our God.

No longer strangers to each other,

no longer strangers in God’s House;

we are fed and we are nourished

by the strength of those who care,

by the strength of those who care.

Station 7 | St. Paul’s Anglican Church, Cnr High & Corundum Streets

The St Paul’s Anglican Church, Stanthorpe, dates from the early 1870s. A bark hut erected in 1872 served as a temporary church building, until a more permanent timber building was erected 1873. The present church building dates from 1957.

We pause here at St. Paul’s Anglican Church to read a little about one of it’s sister chapels at Maryland. In 1887 St. Paul’s Church of England was consecrated at Maryland Station and it was de-consecrated around 1960. It is situated on Leslie Street, off Thulimbah Road, Maryland. A wedding was held in the Chapel in 2020 by the kind favour of the owner. Usually, it is just used to store hay for the stock.

Station 8 | Uniting Church, High Street

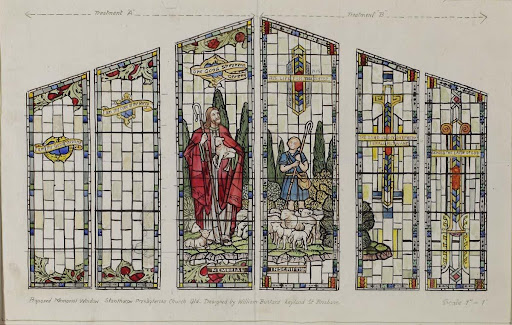

The contemporary Stained Glass windows at Stanthorpe Uniting Church are being built and designed by Owen Ronalds using contemporary paintings of Jesus painted by the late Rev’d David Binns.

There will be nine panels featuring images from the Gospel stories about Jesus.

List of Images Being Created: The Garden of Gethsemane, The Crucifixion , The Empty Tomb

Jesus baptism by John, Calming the Waters, Pilate washes his hands

Healing of a lunatic Boy, Entry to Jerusalem, Cleansing of the Temple

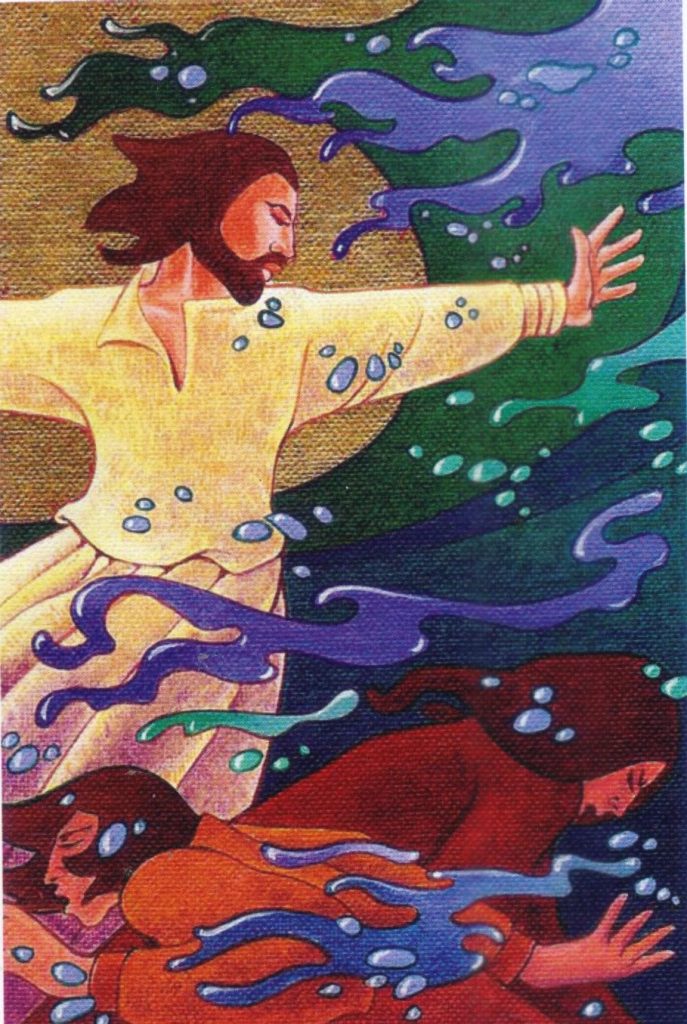

Fr Binns’ painting ‘Calming the Storm’

William Bustard’s design of The Good Shepherd Window

The large window of Christ, the good Shepherd was designed by the prolific English born Brisbane artist, William Bustard. He came from a Victorian tradition of stained glass that sought to create a peaceful and beautiful atmosphere. It was made from a full sized cartoon by tradesmen, perhaps including Oliver Cowley when he worked at Exton’s Glass Company in Brisbane. The horizontal windows along the car park side reminding viewers of bible scenes were designed and made by Oliver Cowley. The pictorial tradition in churches stretches back to an age before images or literacy were common and was an accessible way for the ordinary person to understand and remember bible stories. Jesus is mostly portrayed as white, a cultural reflection.

The windows along the western side were made by Owen Ronalds. They were adapted from the icon like paintings of New Testament scenes created by Anglican Father David Binns. His smaller gilded paintings centered on the story of Jesus. Some of his many images have been gathered into threes to better suit the horizontal space. The first to be completed, after a bequest, was the Calming of the Storm. It speaks powerfully as an allegory for the storms of grief we all have to sail through in life. The stillpoint of Jesus can bring us comfort and hope amidst the waves of despair that can threaten to overwhelm us.

Father Binns used to explain to people how icons were not to be venerated, a common criticism by protestants who were somewhat wary of images as idols. Rather, they are more like a familiar photo of a child or partner that might be carried to bring back to mind the feelings of love and affection. Also a sense of place where we loved to be perhaps? So he would be glad if people found time to simply sit in an attitude of prayer letting the images stir feelings and ideas from contemplative viewing, centring upon the life and actions of Jesus.

Angels feature in some windows and are interesting characters. Their wings, which we nowadays take for granted on angels, indicating that they are not of this real world. They are an external expression of an inner message or comfort.